The month of May celebrates Jewish heritage in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province. One often-overlooked chapter in their rich history is the role of Jews who supported the British crown during the American Revolution.

This article was a collaborative effort by three researchers and writers: Stephen Davidson UE, Stuart Manson UE, and Stephen McDonald UE. All are members of the United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada, and the latter two are members of the St. Lawrence Branch.

The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) was a vicious civil war pitting Rebels against Loyalists. At the beginning of the conflict those living in the colonies were divided in sentiment. Having sided with the defeated British, approximately 60,000 Loyalists left the new United States and sought refuge within King George III’s reduced empire. This ‘Loyalist Diaspora’ resulted in about 7,500 coming to what is now Ontario.

The Loyalist refugees fleeing the United States were a diverse group representing many ethnic, racial and religious groups including the Jewish community. Research has now shown that, like many religious and cultural groups, Jews were found in both Rebel and Loyalist camps. Often they are not identified as Jews in historical documents. Some historians have had to make educated guesses based on predominantly Jewish surnames.

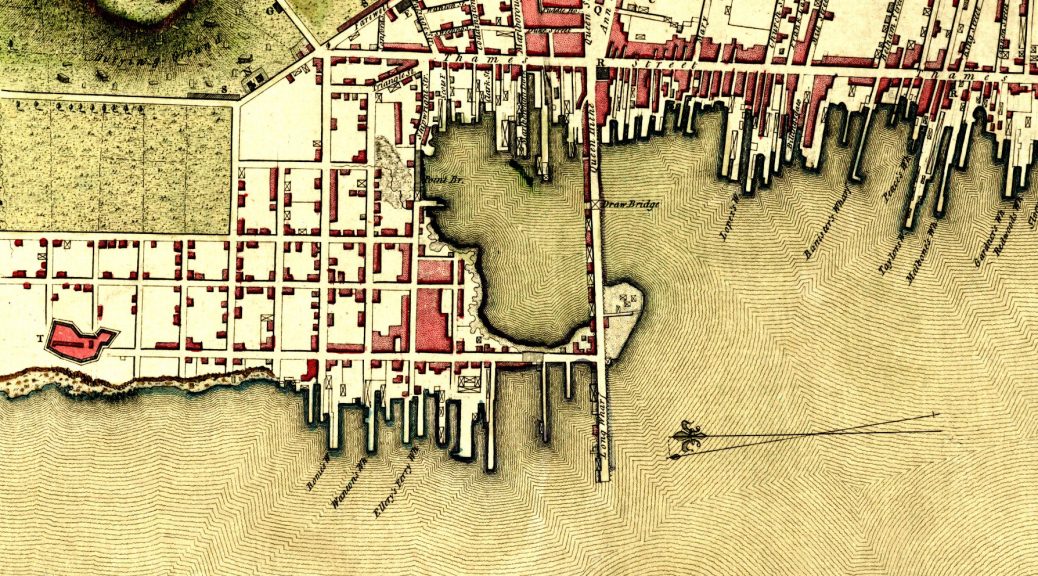

Hart is a common surname among Jews of colonial America and also among those who remained loyal to the Crown during the American Revolutionary War. The Hart family of Newport, Rhode Island were Jewish Loyalists some of whose members did not survive the American Revolution. A period map of Newport is illustrated above. When the British evacuated that city in 1779, the loyal Harts followed them to the New York City area, settling on Long Island. The Rebels later attacked this settlement. Despite a spirited defence in a makeshift fort, Isaac Hart was killed “with the greatest brutality by the rebels for his attachment to Great Britain.”

Samuel Hart was a merchant and politician who lived in Philadelphia and New York City. Hart set up shop in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1785, where his business initially prospered. His biographer notes: “Not content with material success, Samuel Hart aspired to social recognition, even if that required suppression of his Jewish identity”. In March 1793, he was baptised as an Anglican. However, Hart’s mercantile business failed. The subsequent stress was too much, and in 1809 he was declared insane. He died the next year, “a pathetic figure who spent the last days of his life chained to the floor of a room in his Preston mansion.”

Abraham Florentine, a Jew of Italian origin, was a dry goods merchant before the revolution. He had establishments in New Jersey and New York City. A Loyalist, he joined the migration northward, settling in Digby, Nova Scotia. He soon left for England to seek compensation from the government. Unsuccessful, he returned to the United States of America where he appears to have been reintegrated into American society, a rarity for Loyalists who were usually unwelcome in their native colonies.

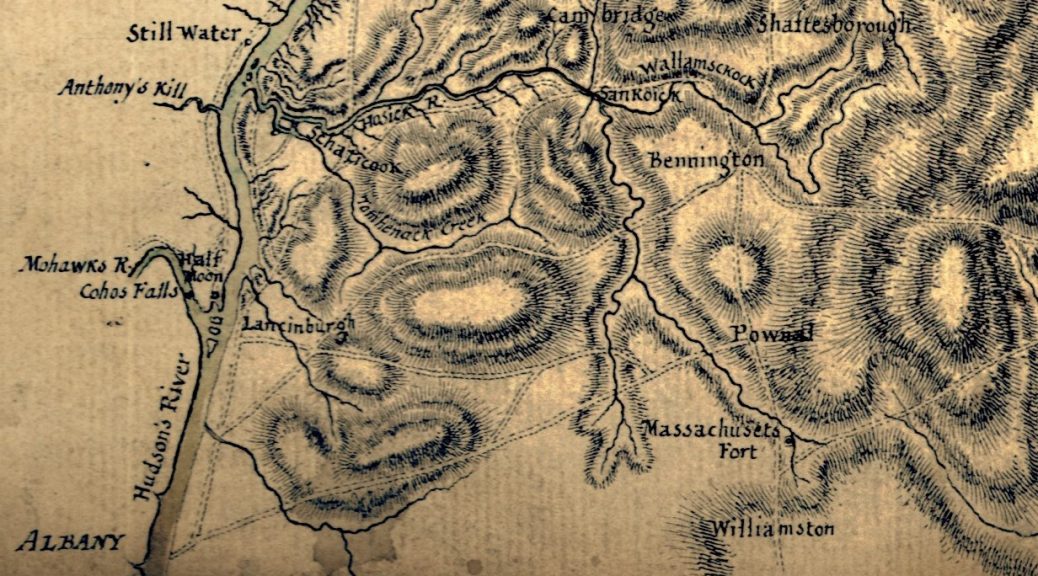

Barrak (Baruch) Hays was a Loyalist Jew who fled to Montréal from New York City in the spring of 1783 where he was reunited with his brother Andrew. Their father, Solomon Hays had emigrated from the Netherlands to the colony of New York in the 1720s. Solomon ran a mercantile business and became a prominent member of New York City’s Jewish community.

Barrak followed in his father’s footsteps, establishing a business based in both New York and Newport, Rhode Island. Andrew, a younger son, decided to take advantage of new business opportunities in Montréal. He settled there sometime after 1769 and became involved in the city’s thriving fur trade.

Colonial Jewish businessmen had a record of providing the British forces with needed provisions during the Seven Years War and did so again during the American Revolution. Some sold military provisions to the British troops and German mercenaries in Canada as early as 1775, while others did the same within the rebellious colonies following the British occupation of New York City in August of 1776. Barrak Hays was one of those businessmen, describing himself as an “auctioneer in the city of New York”.

Hays had taken a strong Loyalist stance in the fall of 1776 when he and 500 other New Yorkers signed their names to a petition to the British for “restoring peace in His Majesty’s colonies”. Hays not only sided with the Crown, he also came to the aid of his synagogue when he learned that the British had plans to turn it into a military hospital. Hays was one of three men who “prevailed on the British not [to] do with the synagogue as they had with most of the other churches in the city. They had turned them into hospitals, riding academies, barracks and things of that kind.”

However, the synagogue did not escape vandalism. British soldiers broke into it, destroyed some of the furnishings, and damaged the Torah and other holy writings. To its credit, the British army publicly whipped the vandals who desecrated the synagogue.

In addition to his business connections with the British army, Hays was employed as an “officer of guides,” receiving five shillings a day for his services until June of 1783. Sensing the inevitable victory of the Patriots in August 1782, Hays decided to go to Montréal. He was there a year later, where he stayed for at least a decade. It seems most likely that he resumed his career as an auctioneer.

Upon his arrival in Montréal sometime after 1769, Hays’ brother Andrew had joined the local Jewish congregation, becoming one of its leading members. In 1777, Montréal’s Jews built themselves a synagogue, Shearith Israel Congregation — the first in Canada.

Montréal’s Jewish community — which now included Loyalist refugees as well as those who remained loyal throughout the revolution—was made up of businessmen, fur traders, and army personnel. It is estimated that 10% of Montréal’s merchants were Jewish. Andrew Hays’ son, Moses Judah Hays, would later become a municipal leader, serving as Montréal’s chief commissioner of police and organizing the city’s first water-works.

Details about the lives of the Loyalists, Barrak and Andrew Hays, begin to peter out after the massive refugee resettlement that followed in the wake of the American Revolution. A list of 113 members of a Masonic Lodge in Newport, Rhode Island “previous to the 24th of June, 1791” includes Barrak Hays’ name. Given that there was a large Jewish community in Rhode Island and that Hays once had a business in Newport, he may have moved there in the hope of establishing a new life in a more promising economic climate.

There are also references to the death of a Baruch Hays in the West Indies on April 13, 1845. This British colony had a fairly large community of Jewish businessmen; it would make sense for the New York Loyalist to have settled in the West Indies. Barrak Hays may have moved from New York to Montreal to Rhode Island and then to the West Indies before the conclusion of a tumultuous life.

David Franks was a merchant from Philadelphia who spent the American Revolution supplying troops — both Patriot and British — with provisions. However, he eventually gave his allegiance to the British crown. Phila, Franks’ socialite daughter, eloped with Oliver Delancey, a prominent Loyalist who had established a three-battalion regiment operating out of New York City. Phila converted to Christianity at the time of her marriage.

During the war, David Franks migrated to Montréal, and joined its Jewish community. He contributed to the construction fund for Montréal’s first synagogue. Seeking compensation for the sizeable losses he sustained during the war, Franks left Montreal for England. There he died there within ten years of the revolution’s end, still suffering financially. A key biographer claims: “David Franks deserves to be numbered among Loyal Americans who suffered greatly during the American Revolution, and his story is an example of the tribulations that could befall a civilian Loyalist in those difficult times”.