In the autumn of 1783, the American Revolutionary War was over. In Québec and in other British-held areas, thousands of refugee Loyalists were now permanent exiles from their former homes in the new American republic. British administrators hastened to find lands that were agriculturally fit for their resettlement in the remainder of British North America.

Québec Governor Frederick Haldimand, a key figure in this effort, looked westward towards the upper St. Lawrence River. He sent men to explore and to report on the area. The report of one such explorer, described below, offers an early glimpse of the lands that later became the Loyalist settlements covered by our branch of the UELAC.

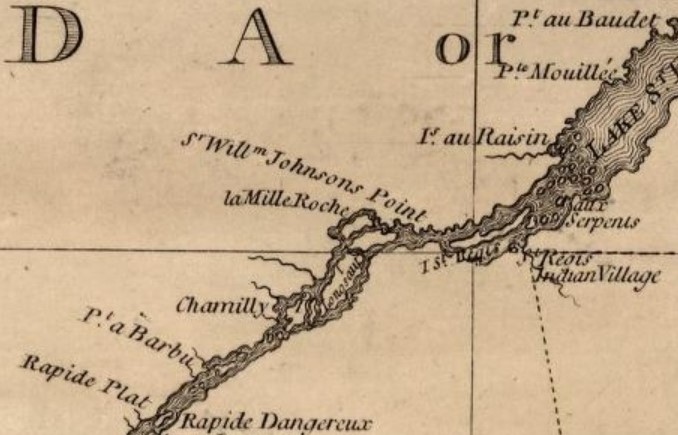

The author of the 1783 report, unknown because he did not sign his oeuvre, travelled west up the St. Lawrence River, beyond the last French Canadian settlement at “Pointe au Beaudet” (present-day Rivière Beaudette, Québec). The lands are those depicted below, in a 1776 map of the region.

His impression of the first lands he saw, which later became the Township of Lancaster, was mixed: They were “interspersed with swamp and drowned lands,” he reported about those near the river. Inland from those moist areas, however, the land was “very good for three miles back,” and in some cases “excellent” with stands of pine and hay meadows. Nonetheless, other parts of the same area he described as “very wet and swampy.” Hence the reference to Lancaster as the “sunken township,” and its most prominent headland as Pointe Mouillé.

His impression of the first lands he saw, which later became the Township of Lancaster, was mixed: They were “interspersed with swamp and drowned lands,” he reported about those near the river. Inland from those moist areas, however, the land was “very good for three miles back,” and in some cases “excellent” with stands of pine and hay meadows. Nonetheless, other parts of the same area he described as “very wet and swampy.” Hence the reference to Lancaster as the “sunken township,” and its most prominent headland as Pointe Mouillé.

Our explorer, continuing westward, then reached the Raisin River near the boundary between present-day Lancaster and Charlottenburgh townships. He ascended this significant stream for several miles, to a waterfall suitable for a mill (present-day Williamstown). “From the lake to the falls the land for the most part is bad, except some points,” he reported. This area was not without notable attractions; nearby he had cast is eye upon “the largest cedar I ever saw.”

Better lands were evident as he moved further west along the St. Lawrence River. Between Raisin River and Mille Roches, which covered all of present-day Charlottenburgh Township and a good part of Cornwall Township, he considered the land “excellent” for three to six miles back from the river. The soil was deep and the forests offered a variety of species such as maple, hickory, beech, white oak, and bitternut. He was less impressed with the area immediately west of Mille Roches, near the boundary between present-day Cornwall and Osnabruck townships: “For the most part bad, having much broken ground and a pine ridge, the soil is light and stony near the river, but a mile back the land is good.”

He then trekked further west to the area covered by present-day Osnabruck Township. He liked what he saw, and was particularly enthralled with a large “pine flat” that contained plenty of good timber and was surrounded by good land.

As he ranged further westward, near what is now the townships of Matilda and Williamsburgh, it was clear that Nature saved the best for last. He described the land as “as good as any I ever saw, it is well watered with several fine creeks.” He considered this region to have the largest acreage of lands suitable for settlement.

After reading this and other reports, Governor Haldimand was optimistic. He wrote in an official report to Britain that the districts pegged for Loyalist resettlement could produce “great quantities of wheat and other grains and become a granary for the lower [downstream] parts of Canada.” In the end, the lands on the upper St. Lawrence were surveyed as “Royal Townships” for the Loyalists, but they would suffer many hardships before attaining the lofty predictions of the governor.

The historical content of this page was researched and presented by Stuart L. Manson. It is subject to copyright; no reproduction without permission.