Descendant of Oriskany

by Sean Rombough

This story originally appeared in the Loyalist Trails newsletter (Vol. 2022-40, 2 Oct 2022).

I’d been driving for about 6 hours from Ottawa before finally arriving at the Oriskany Battlefield State Historic Site. The entrance gate was an unassuming exit from NY-69 and I’d managed to cruise past on my first attempt to find it. The sign attached at the gate read that it would be closing in 20 minutes so I moved quickly from the parking lot for a closer look at the monument and then down to the tiny visitors centre at the base of the hill behind the 93-foot obelisk.

After a brief conversation about my connection to the events there, a worker and I chatted about what may be planned for the approaching 250th anniversary of the battle. Surprisingly, nothing had been proposed for what I’d expected would be an important commemoration in a country nostalgic for its patriotic history. In fact, I’d half-expected to drive up to a major tourist destination having been to many other American historic landmarks. That day, however, there was none of that to be found.

I explained my involvement with the St. Lawrence Branch of the United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada, and I suggested the anniversary might be an opportunity for descendant cousins from both sides of the battle to come together and recognize the tragedy that had occurred that day at Oriskany. After all, I explained, even the Mohawk and Oneida communities might be interested in attending for the sake of their ancestors too.

He looked at me sheepishly with a mix of concern. He seemed worried he might come across as offensive and looked disappointed that he could not offer the answer I had hoped for.

“I don’t think that will EVER happen sir.”

Clearly the wounds of this place have not healed.

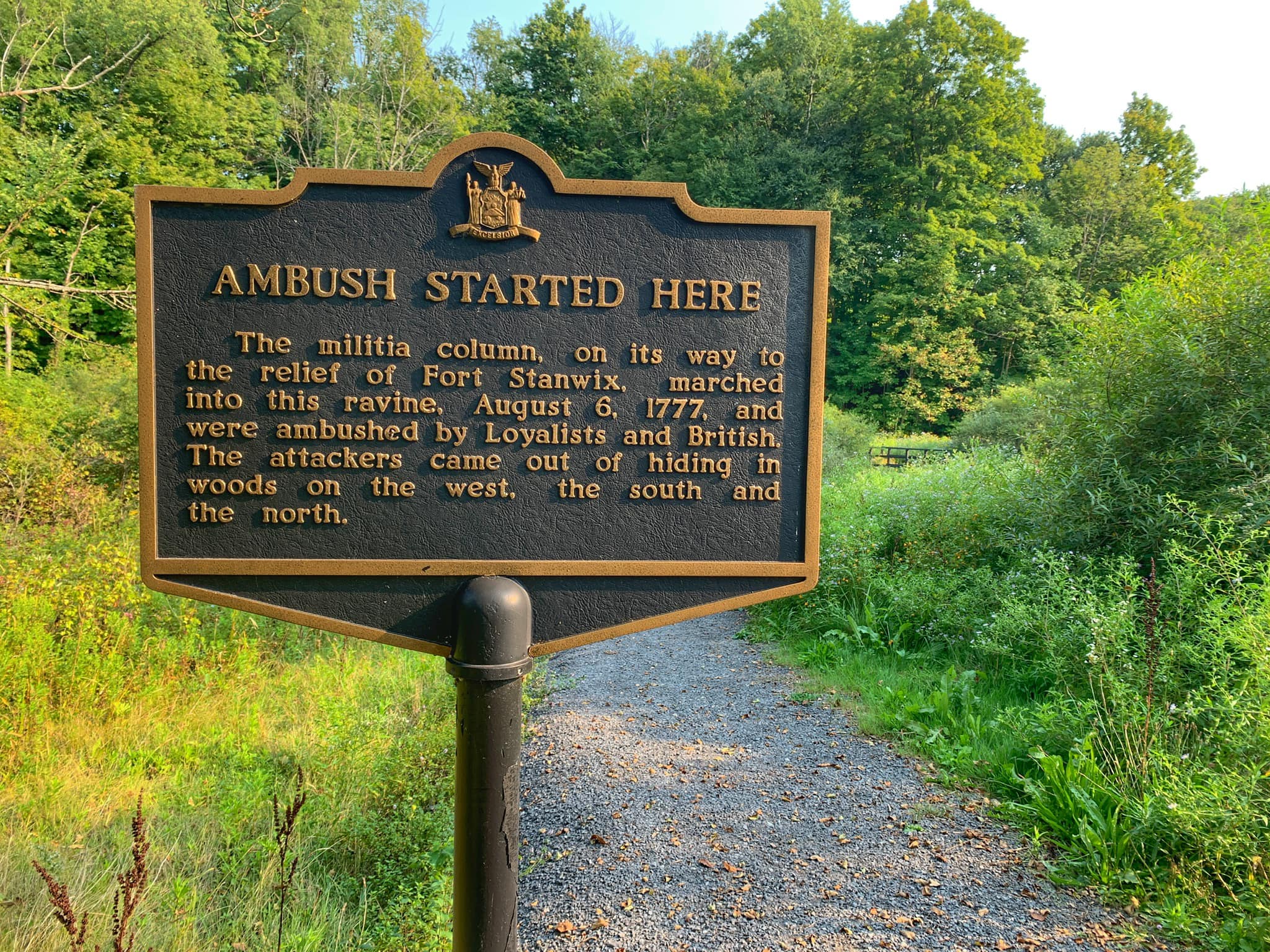

After being reassured that the gates would remain open past the posted closing time, I wandered around the grounds and found myself walking the path taken by the Tryon Militia and their Oneida allies on August 6th, 1777. At least two of my great uncles, John Countryman and Heinrich Fetterly, were part of that group led by “Patriot” Brigadier General Herkimer. Unbeknownst to them, they were walking into an ambush.

Above and almost completely all around the militia were Mohawk, Seneca and Loyalists who’d been exiled from their homes. They’d returned to the Mohawk Valley as members of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York. Sixth and seventh great grandfathers, Jacob Countryman (John’s brother) and Michael Warner, had just joined the regiment a few months earlier, but it’s difficult to know if they were there too.

The first shots were followed by hours of some of the most brutal and bloody fighting of the entire war. A second wave of fighting is said to have been hand-to-hand and terrifyingly personal as simmering grievances between former neighbours had reached their violent end. When it was over, around 400 militia men, including my great uncle Heinrich Fetterly, were dead. Less than a quarter of that number were killed on the Crown side but both groups abandoned the bloody ravine that day. The Loyalist forces scrambled to defend their camps which had been raided from Fort Stanwix. What was left of the militia dragged itself to safety. Both sides left most of their dead behind and when Major General Benedict Arnold’s Continental Army relief force passed through the area 18 days later, decaying corpses lay all around. That ugly scene marked the escalation of bitter hostilities and incredibly tangled allegiances in the Mohawk Valley.

Heinrich’s brother Philip Fetterly was my 7th great grandfather. He served alongside one son in the Albany Militia. Another son, John, was my 6th great grandfather. He was jailed for Loyalist sympathies. John’s younger brother, Peter Fetterly, joined the King’s Royal Regiment of New York alongside six more of my great grandfathers. In 1780, my Loyalist great grandfather Jacob Countryman’s older brother Frederick was killed by Loyalist raiders at Minden, New York. All together, 26 of Jacob’s brothers and nephews fought against him for the rebel cause. Three more of my great grandfathers joined the fight as Rangers under John Butler and Daniel Claus. All of them fought former family and friends before being forced out of the smouldering Mohawk Valley after the war.

“Tangled” family allegiances may be too pleasant a word. “Mangled” may be more appropriate.

Standing at the Oriskany Creek in that ravine in 2022, I have to admit to being overwhelmed by it all. Again, I had not expected to visit such a bitterly serene, yet consequential, place. This ravine I’d read so much about was indeed too solemn to desecrate as some simple tourist attraction. I looked over to see an apple tree not far from the path and was repulsed at the thought of someone eating from it as I recalled accounts of the creek running red with blood.

The grandeur of the grey obelisk in the distance, despite its towering presence in the open field, paled in comparison to the quiet, bubbling of the creek below me and the wind in the trees all around. Was that peace I was hearing or something unsettling? Was it both?

The worker had explained to me that, unlike so many other historic battlefields, reenactment activities are forbidden at the site. Oneida leaders consider it sacred ground. Walking back to my car that afternoon I wholeheartedly agreed. Peace may someday come to Oriskany. But it will take more than the suggestion of a descendant of its outcome for that to happen.