The catchment area of the UELAC St. Lawrence Branch is located in the territory of the Mohawks of Akwesasne, whose history and culture we would like to recognize.

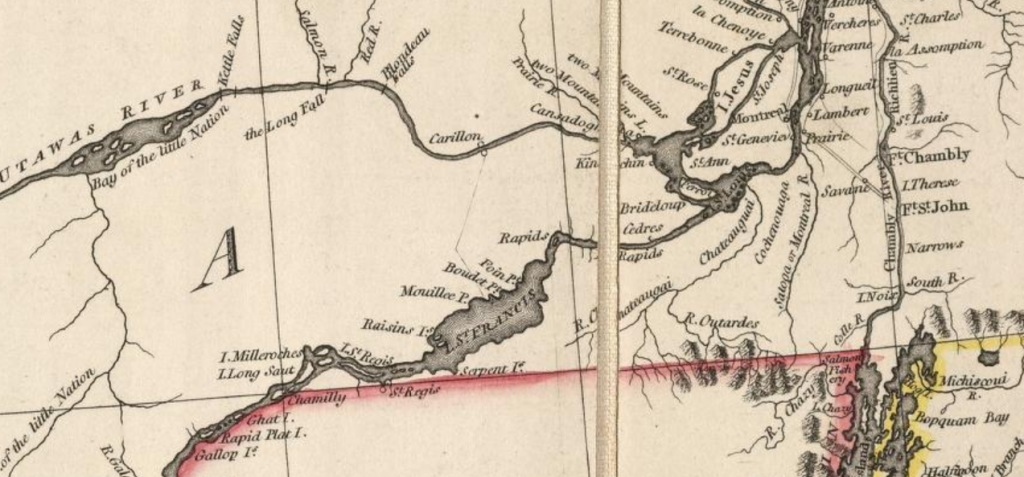

The people of Akwesasne are part of the larger Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) nation. The community is centred around the village of St. Regis, established on the south side of the St. Lawrence River, south-east of Cornwall, in 1755. That settlement was then established when a group migrated from Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) near Montreal, who in turn had migrated from the Mohawk River and Finger Lakes region several decades before. Oral history and archaeological evidence, however, indicates that the Haudenosaunee occupied the St. Lawrence Valley well before that date, in pre-contact times.

The story of Akwesasne during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) is rich with significant events and deeds. While its history is complex and multi-faceted, early in this conflict, many of its people joined the fight against the rebels.

In late 1775, warriors from St. Regis opposed the rebel General Richard Montgomery’s advance against the British post of St.-Jean-Sur-Richelieu, south of Montreal. This was part of the rebel invasion of Canada. In one instance during this campaign, men from St. Regis were part of a detachment of 100 loyal combatants who repelled an attempted amphibious landing of 1,400 rebels.

A French Canadian officer in this detachment, Claude-Nicolas-Guillaume de Lorimier, cited the presence of a St. Regis chief during the campaign. His name was “Hotgouentagehle,” and de Lorimier called him his “great friend.” He was likely the Onondaga warrior “Ohquandageghte,” who was more associated with the village of Oswegatchie (present-day Ogdensburg, NY), before he settled at St. Regis prior to the American Revolutionary War. Unfortunately, in the fall of 1775, the chief died of a bullet wound to the leg. He gave his life defending Canada from invasion.

Early in the spring of 1776, while Montreal was still occupied by the rebels, de Lorimier assembled a force of Indigenous warriors to strike at the rebels’ western flank. The village of St. Regis was an important rallying point during this campaign. According to de Lorimier:

“The next day we set out and arrived at St. Regis at about two o’clock. Our flotilla of small canoes was more impressive than one might have thought. When we got near the village we fired off a fusillade accompanied by every imaginable shriek of joy (the effect was horrifying) and each nation sang its death song. We were well received and were housed in large buildings made of bark. That night I made a feast at which two oxen were roasted. We sang the war song and all the warriors of the village joined in. After that there was nothing more to do, so when the moment came we left the village…”

The force, with a significant party of warriors from St. Regis, later successfully forced the surrender of a superior rebel force posted at The Cedars, near Montreal. They also skirmished with rebel relief parties, and joined recently-arrived British troops, who lately liberated Montreal, in the pursuit of the retreating rebels as the fled southward into New York.

The village of St. Regis was also directly involved in another event of significance in the early part of the war. In June 1776, a party of 170 men emerged from the forest and entered the village. The party was headed by Sir John Johnson, a Loyalist who had narrowly escaped capture by the rebels in the Mohawk Valley in the colony of New York. At St. Regis they refreshed themselves after their long and arduous journey, before continuing on to Montreal.

It is also interesting to note that, on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence characterized Indigenous groups in a very negative light. That document did not specifically refer to the Haudenosaunee, but the historical context of the period indicates that they were the main subject of the unfair characterization. It referred to “…merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions.”

St. Regis warriors were present in other raids into New York, in particular one in 1780 whose target was the area around Fort Stanwix, and the head of the Mohawk River. There they skirmished with the garrison, successfully taking several prisoners before the rebels retreated to the safety of the fort.

By 1783, hostilities ceased. The war officially ended that year with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Quebec Governor Frederick Haldimand had several thousand displaced Loyalists on his hands, refugees from the Thirteen Colonies. He sent surveyors into the St. Lawrence River valley to survey new settlement lands for these Loyalists. For this land, Haldimand made land cession treaties with the some Indigenous peoples, but neglected to do so with the Mohawks of Akwesasne; their leaders quickly informed the Crown of their error.

Negotiations ensued, which resulted in a treaty arrangement, albeit poorly documented, in which the Mohawks of Akwesasne received compensation in the form of additional reserve lands. These included a strip of land on the north shore of the river, between Charlottenburgh and Cornwall Townships (then known as Royal Township Nos. 1 and 2). This opened the path for Loyalist settlement and peaceful coexistence, which began in the spring of 1784.