(first published in The Loyalist Gazette, Autumn 1983 at pp. 11-12)

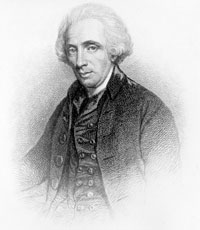

William Smith was the most intellectual of the Loyalists and one of the few to achieve eminence in both the old colonies and the remaining loyal provinces. There is little doubt that if Smith had not been a Loyalist, he would have been one of the framers of the American Constitution. Although a Loyalist, Smith was in no sense a Tory. He shared the ideas of the mainstream of American liberalism, had, like his father, attended Yale, and enjoyed a distinguished career at the Bar. Smith was of Presbyterian background and the son of a Huguenot mother. Having been assimilated, in this sense, to the melting pot, he believed that all North Americans should accept some form of the Protestant faith and speak English.

Born on 18 June 1727, he studied law and began his political life by joining a campaign against the establishment of King's College, New York, later Columbia University. He saw this as the first move in an effort to establish an Anglican episcopate in America which, he believed, would lead to the creation of an exclusive and monopolistic Anglican establishment in the colonies. It is significant that in this battle, Smith supported the losing side, but established his place as a political controversialist by doing so. When the quarrel over colonial taxation broke out, Smith became known as "Patriotic Billy" because of the vigour with which he denounced British policy. Meanwhile, he married a daughter of the Livingston family, one of the wealthiest in New York and strong supporters of the colonial cause.

When armed resistance broke out, Smith gave up articulate protest and sought the larger role of mediator between the Crown and the Continental Congress, seeing in the outbreak of hostilities an opportunity to secure the acceptance of a plan of confederation which he drew up, based on the Irish Constitution. There would be a Lord-Lieutenant of America, an appointed upper house and an elected lower house. Essentially an executive, Smith was a man of ideas rather than a politician. He misjudged the mood of the Continental Congress which was seeking foreign allies, not compromise. Yet Smith tried to maintain his position as a neutral under the government of the Continental Congress until 1778 when he was given the choice of taking an oath to New York State or moving into New York City, then under the control of Crown forces.

When forced to choose, Smith joined what he considered to be the cause of liberty and order, and moved behind the British lines. He had not been impressed by the quality of government under the Continentals, and conceived the idea of providing in New York City a model of good government which, by force of example, would demonstrate the folly of revolution. Under wartime conditions, however, the quality of government inevitably deteriorated on both sides of the lines. When Sir Guy Carleton took over command in New York in 1782, Smith was made Chief Justice and hoped for a while that he might be able to carry out his experiment in providing exemplary government. This proved impossible because New York was under military government and, as long as this lasted, Smith, as civilian chief justice, could exercise very little authority.

At the end of the revolution, Smith resided in England for a while and found himself very much at home in the company of radical intellectual circles in England, including those who had supported the cause of colonial independence. For some time, his future was in doubt, but he had gained the confidence of Sir Guy Carleton who, after being raised to the peerage as Lord Dorchester, returned to Canada as governor-general, the titular head of all British-American provinces, but in practice the governor of the old province of Quebec which included present-day Ontario. Dorchester secured for Smith the appointment of Chief Justice of Quebec. When Dorchester set sail from Portsmouth on 29 August 1786, his entourage included the new chief justice and his son, William, and a manservant. His wife, Janet, and two daughters, Harriet and Mary, were still in New York City, planning to take ship in the spring to join him at Quebec City.

Having begun his political life as a controversialist, Smith had learned to accept defeat as part of the natural order of things. He was, above all, an architect of political designs and when one design was rejected, he prepared another. Once his scheme for federation of the old colonies became obsolete with colonial in- dependence, he devised a new one for the federation of the remaining loyal provinces. There would be a viceroy of British North America who would be in charge of Anglo-American relations with power to appoint consular officials in the United States. If wartime New York could not be turned into a model of exemplary government, then a post-war federation of loyal colonies must be established which would provide a superior form of government, capable of attracting non-Loyalist American settlers and ultimately drawing the wayward colonies back to the Empire.

The authors of the Durham Report in 1838 studied Smith's plan carefully and recommended a federation of the colonies, but even in Durham's time, schemes for federation were premature. With small pockets of population in a vast territory, it was easier to tax and govern at the provincial level and leave the larger questions of defence and foreign policy to the imperial government and on the imperial budget.

Once in Quebec, Smith put aside the large plans and concentrated on local improvements. Here he found a good deal to occupy his mind. The province was governed by an appointed Council, drawn up, for the most part, from local residents. At the time of Smith's arrival, it was dominated by the "French Party" which included some seigneurs, but was led by the Scot physician, Adam Mabane. The policy of this party was embodied in the Quebec Act of 1774. According to the views of this party, Quebec was and would remain French and the small English population would live as a minority under French civil law, within the framework of the seigneurial system of land-holding, and conducting most of its business in French. This party was opposed by the "English Party", made up of merchants who believed that the adoption of English laws, a freehold system of land-holding, and the use of English in the conduct of public business, would attract settlers from the old colonies. The absence of such immigration in the years before the revolution seemed to have ensured the final defeat of the English party, but their hopes rose again when Loyalist immigration increased the English element from four to fourteen percent of the population.

Before the arrival of Smith, Peter Livius, who had been a judge in New Hampshire, was made Chief Justice of Quebec. He challenged Mabane's party and had been dismissed in 1776. At the time of Smith's arrival, another New England judge, James Monk, was fighting his last battle with Mabane. There could be no doubt but that Smith would side with the English party. In doing so, he brought to their assistance a more acute intellect and wider experience than had hitherto appeared in their midst. Moreover, Smith seemed to have still the confidence of Dorchester who was impressed by Smith's ability to devise large schemes. The difficulty was that Dorchester had been the sponsor of the Quebec Act. Thus he could not accept Smith's grand designs without repudiating his former policy.

Being half French and wholly assimilated, Smith believed that French Canada should be dissolved into a continental melting pot. With this in mind he planned to create a system of universal education which would offer the habitants an opportunity of learning English by means of elementary schools at the parish level, secondary schools for the counties, crowned by a university at the provincial level. All this was to be financed by revenues of the Jesuit Estates, which were then unassigned and under the control of the Crown. Smith's university would he secular and consequently unacceptable to both the Catholic Bishop of Quebec and the Anglican Bishop of Nova Scotia who exercised jurisdiction in Quebec.

Undismayed, Smith proceeded with his campaign to win control of the Legislative Council from Adam Mabane's French party and won in 1791. However, his victory was short-lived. The passage of the Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the old province of Quebec into Upper and Lower Canada, thus nullifying the effect of Smith's victory over Mabane's party. Smith had hoped to use the ballast of the Loyalist settlers in what became Upper Canada to secure the abolition of the seigneurial system of land-holding and of French civil law. He was still convinced that this would bring a flood of American immigrants to Canada and finally provide an opportunity to demonstrate the superiority of British over republican institutions.

The Loyalists on the upper St. Lawrence

had no such dreams. Their most eminent representative, Sir John Johnson

in Montreal, was content to secure a separate province which would have

the laws and system of land-holding that had existed in the old colonies.

Dorchester declined to support or oppose Smith's projects for reversing

the policy of the Quebec Act of 1774. The decision was thus left to London

and the partition of the province seemed to be the line of least resistance.

With this final defeat, Smith's career was drawing to a close. He died

6 December 1793 with one consolation: The Eastern Townships were thrown

open to American settlement. They would still be under French civil law,

but would have a freehold system of land tenure. It would be wrong to

see in the failure of William Smith's schemes a failed career. Smith remained

close to the centre of power for most of his life and died in high office.

Like many intellectuals in office, he had a vision of the future which

led him to support projects like Canadian federation which were far ahead

of his times. Similarly, his confidence in what he conceived to be enlightened

thought made it difficult for him to comprehend the value and permanence

of French culture in North America and the deep roots of the Catholic

faith.

Smith had the virtues and failings of a liberal intellectual - faith in the power of reason and a somewhat optimistic view of what reason could accomplish. It was this quality of mind that made him a Loyalist because he could not see in the revolution a triumph of reason.

By Prof. Hereward Senior

Department of History, McGill University

Honarary Vice-President, UELAC