Saturday, January 26, 2019

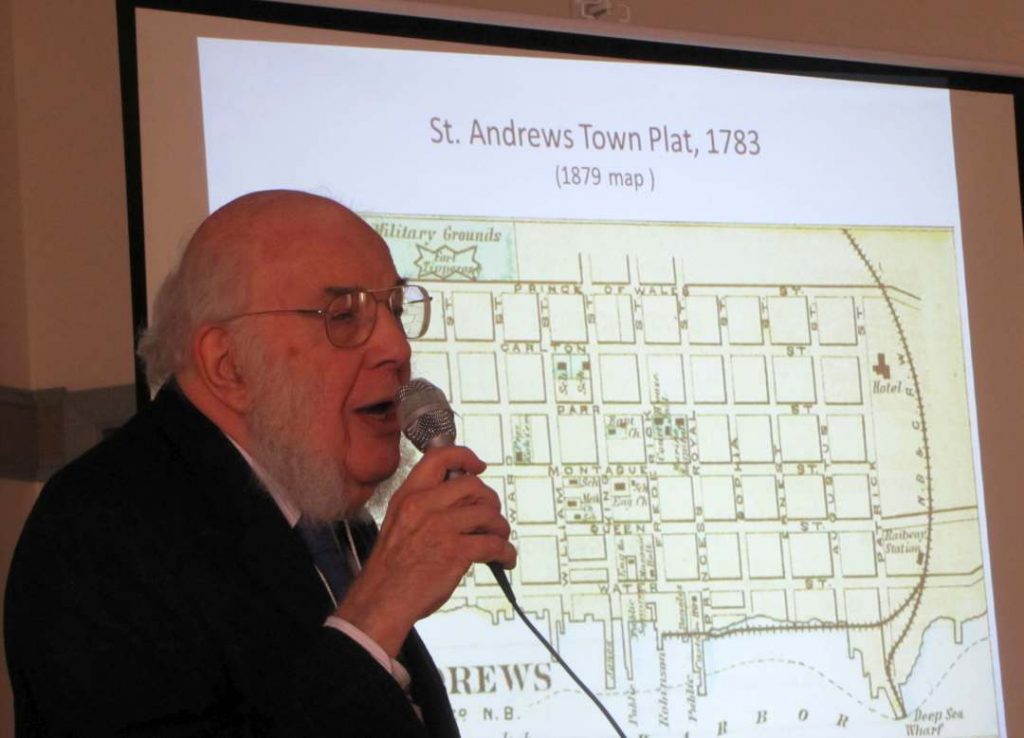

Despite the cold, some 24 hardy souls enjoyed a hot lunch of stew and trimmings. They were then joined by eight or ten others including several visitors, to hear Dr. Leigh Smith speak on “Take Up Your House and Sail!” – the story of Loyalists from Castine, Maine who moved their homes to St. Andrew’s, New Brunswick.

When the Maine/Nova Scotia boundary was finalized after the Treaty of Paris (1783), it turned out that the town of Castine was to remain in the State of Maine, instead of the Province of Nova Scotia. (New Brunswick had not yet been carved out of Nova Scotia: that came in 1784.) About 40 Loyalist families from Castine carefully took apart their wooden houses, laid the walls and roofs onto barges, and floated them down the Penobscot River, along the coast through Passamaquoddy Bay, and up the St. Croix River to the spot where St. Andrew’s took shape. Dr. Smith was able to show photographs of several buildings still existing in St. Andrews which originated in Castine. He pointed out that these were not log houses, but built of vertical planks of wood, so it was easier to take down each side of the house as a unit. As one member of the audience pointed out, based on the construction methods of the times, they would have been held together with wooden pegs rather than nails, so tapping out the dowels was probably easier than removing nails would have been. Given the tides in the Bay of Fundy, safely moving the barges and their loads was probably the hardest part of the enterprise.

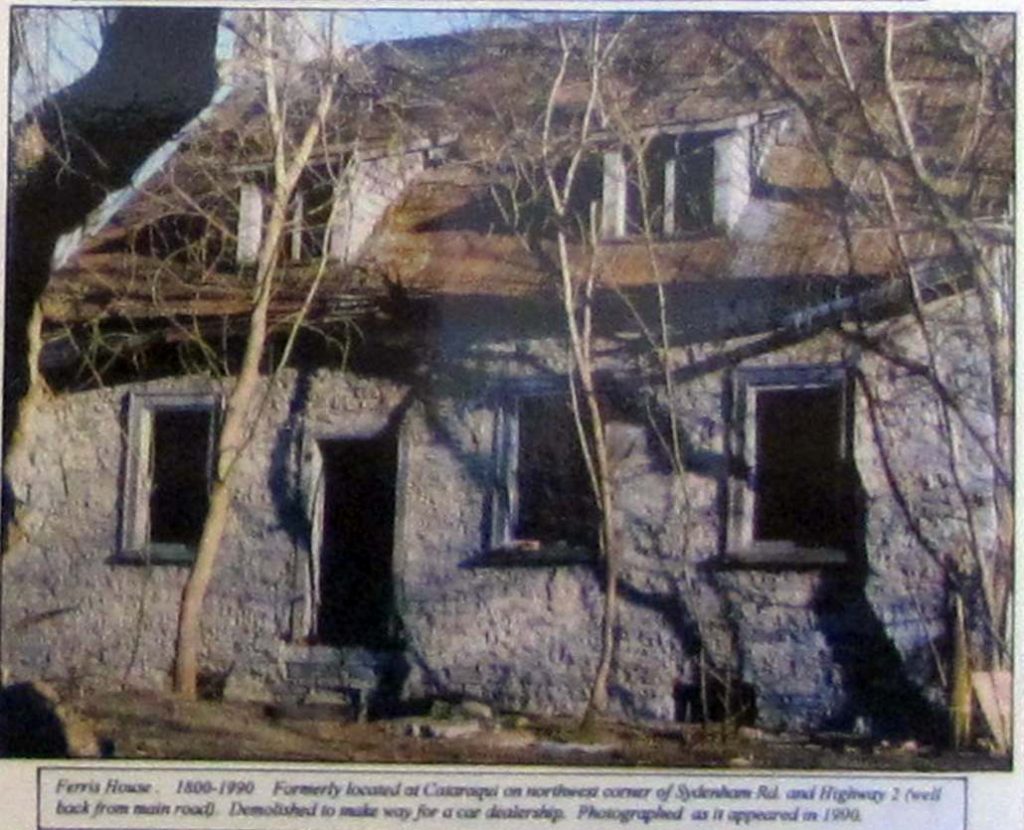

And speaking of old houses … at our November, 2018 meeting someone asked speaker Ruth Nicholson if the Ferriss family she was discussing had any connection to the Loyalist Ferris family who settled in the village of Cataraqui. She was unsure of any connection, but this spurred member John Lynn Bell to dig out an old photo he took of the Ferris house before it was demolished in 1990 to make way for a car lot.

Saturday, March 23, 2019

Our speakers were Angela and Peter Johnson who are jointly the Dominion Genealogists for UELAC.

Their talk was entitled “Documenting your Loyalist Ancestor”. When proving Loyalist descent, the goal is to document each generation, e.g. that you are your mother’s daughter, that she was her father’s daughter, etc. The first rule-of-thumb that Angela and Peter articulated was “Look first for primary sources. These are the registrations of births, marriages and deaths. They are the only sources that stand alone.”

Other sources which can provide information on relationships include, but are not limited to,

- census records, some of which go back to 1803

- Baptismal records are very helpful, when they give the names of parents

- Wills are also an important resource because they name the children of the testator

- Land Petitions. In a petition, the petitioner explains why he is entitled to land or why he should receive even more land than already granted. Upper Canada Land Petitions are all available online, and they are free. The researcher should look not just at the petition but at the outside cover, because that’s where it states what the petitioner got. Was his petition successful, partly successful, or did it fail?

- Family Bibles are another valuable source. However, the researcher is advised to check the title page to find out when the Bible was printed. The listing of a birth, marriage or death that occurred years before the Bible was even printed obviously carries no authority.

- Grave markers in old cemeteries often give information about the family of the person buried there.

- Loyalist regiment discharge certificates are another source, though of varying value. Those of the King’s Royal Rangers of New York contain many helpful details, such as the discharged soldier’s parents’ names and where he came from. The discharge papers of Butler’s Rangers, on the other hand, contain little detail. Regiment Muster Rolls are also of significant help.

- War Losses Claims, which are available on “Ancestry.ca”, may yield useful information.

Peter and Angela warned the audience that the same Christian name was often given frequently within the same family, so that care must be taken not to confuse father, son, uncle, cousin or nephew who all have exactly the same first and last names.

Their talk was followed by an extended question period.