December 5, 2015

We held a Silent Auction which began prior to lunch and lasted until the Speaker stepped up to the podium. These were mostly duplicates removed when our Branch Library was placed at the Central Branch, Kingston Frontenac Public Library, plus a few donated items. Thanks to all who bid and congratulations to the successful bidders: we successfully raised $130 and have reclaimed some much-needed space in our cabinets.

We held a Silent Auction which began prior to lunch and lasted until the Speaker stepped up to the podium. These were mostly duplicates removed when our Branch Library was placed at the Central Branch, Kingston Frontenac Public Library, plus a few donated items. Thanks to all who bid and congratulations to the successful bidders: we successfully raised $130 and have reclaimed some much-needed space in our cabinets.

Our framed Branch Charter is now hung at each meeting. Doris Wemp and Barb Carson help show it off.

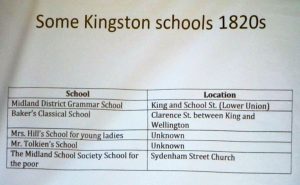

Our speaker was Mr. Gord Sly, a retired schoolteacher and an active volunteer at the Frontenac County Schools Museum, who spoke about Education in 19th Century Ontario. Mr. Sly kindly brought a fine display of photos and artifacts from earlier times. Much more is available at the Museum. Its hours vary during the year, so you should check its website before visiting, and perhaps call the telephone number listed, particularly if you are interested in doing some research into a particular school or area.

Education was rather haphazard and variable from town to town until the appointment in 1844 as Chief Superintendent of Education for Upper Canada of Edgerton Ryerson, a former Methodist missionary and editor of the Christian Guardian. Ryerson believed strongly in universal education. He instituted a standard curriculum across the province, based in large part on what was offered in Ireland at the time.

Even after that, teachers often had no formal training or certification. Senior students helped junior students at school and were then asked to become a teacher. There were no grade levels until 1930: the system went by “book level” and there were 4 books to work through before finishing school.

Mr. Sly described several interesting lists of rules for teachers. A male teacher could not get a shave in a barbershop: that was considered decadent. Teachers were expected to be models of decorum, and “on call” 24/7. Most could not afford their own accommodation and boarded with a local family, often being expected to assist with chores as well. There was no job security: they had to be approved each year by the school truetees, who often chose someone less experienced who could be paid less.There is much material at the museum collected from many schools. Perhaps someone will find a photo of their ancestor or relative among the many class photos.

The number of questions indicated a high level of interest in Mr. Sly’s presentation.

September 26, 2015

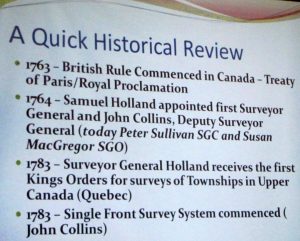

Our speaker was Mr. Nigel Day, OLS, OLIP, Head of the Geomatics Section at the Ministry of Transportation, Eastern Region, who gave a most interesting talk about early surveying of the lands pre Loyalist settlements.

Most of us have had difficulty relating the fact that an ancestor had land on, say, Lot 5, Concession 6 to the actual land: where exactly was that lot? Nigel explained how surveying and other geomatics skills can more easily locate this information today. For some background, Nigel first showed us how his department was able to confirm the location of a portion of the Addington Road near Kaladar, opened in 1861 as a colonization road — it was a Road that would have helped settlers get onto the land. It was most probably used by horse or horse and trap and likely fell into disuse once the motor car came along. By comparing the surveyors’ notes from the time with current aerial photographs, they could pick out where the remains of the early road were. When searching on the ground in the area, remains of the road bed became evident, along with stone walls and even steps. He showed a rusted horseshoe and an empty glass cod liver oil bottle found along the faint vestiges of the road as well as photos of what was found.

Most of us have had difficulty relating the fact that an ancestor had land on, say, Lot 5, Concession 6 to the actual land: where exactly was that lot? Nigel explained how surveying and other geomatics skills can more easily locate this information today. For some background, Nigel first showed us how his department was able to confirm the location of a portion of the Addington Road near Kaladar, opened in 1861 as a colonization road — it was a Road that would have helped settlers get onto the land. It was most probably used by horse or horse and trap and likely fell into disuse once the motor car came along. By comparing the surveyors’ notes from the time with current aerial photographs, they could pick out where the remains of the early road were. When searching on the ground in the area, remains of the road bed became evident, along with stone walls and even steps. He showed a rusted horseshoe and an empty glass cod liver oil bottle found along the faint vestiges of the road as well as photos of what was found.

The law states that what matters regarding boundaries is typically where the first markers are placed during the original survey. Loosely, after the first marks are placed and persons occupy the land, the original monuments override any erroneous distances or directions that were supposed to be laid out by the early surveyors. Distances and directions could vary due to site conditions, magnetic anomalies, human error and other factors. The first surveyors were issued instructions of where to commence and how to proceed. Sizes of lots were dictated and lots were laid out according to those instructions. The presentation outlined some research to date (admittedly far from complete) pulling together early maps, reports, notes and modern aerial photography to show what the original survey looked like and which were the original roads in the area. Additionally, the idea was to present some interesting findings and some items that could be considered unusual and where further research is needed simply to understand how this first township was surveyed and settled.

The law states that what matters regarding boundaries is typically where the first markers are placed during the original survey. Loosely, after the first marks are placed and persons occupy the land, the original monuments override any erroneous distances or directions that were supposed to be laid out by the early surveyors. Distances and directions could vary due to site conditions, magnetic anomalies, human error and other factors. The first surveyors were issued instructions of where to commence and how to proceed. Sizes of lots were dictated and lots were laid out according to those instructions. The presentation outlined some research to date (admittedly far from complete) pulling together early maps, reports, notes and modern aerial photography to show what the original survey looked like and which were the original roads in the area. Additionally, the idea was to present some interesting findings and some items that could be considered unusual and where further research is needed simply to understand how this first township was surveyed and settled.

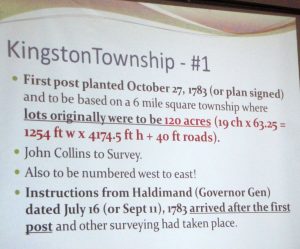

Kingston Township, known as #1, was the first township survey in Upper Canada. A question was posed as to whether it might not be the first fully completed survey, because of some of the discrepancies he has noted. Even though one copy of one set of original instructions exists, the resulting lot system was altered in comparison to those expectations. There was quite probably a different set of instructions also issued which have not yet been located. Additionally, the original field notes are missing. The lot size given in the instructions to the surveyors by John Collins changed during the first year. Nigel showed a copy of a document which has the date of 17 May 1782 at the end above John Collins’ signature, but has Sept. 11, 1783 on the cover page which adds to the complexity of clearly understanding how the survey and settlement proceeded.

Kingston Township, known as #1, was the first township survey in Upper Canada. A question was posed as to whether it might not be the first fully completed survey, because of some of the discrepancies he has noted. Even though one copy of one set of original instructions exists, the resulting lot system was altered in comparison to those expectations. There was quite probably a different set of instructions also issued which have not yet been located. Additionally, the original field notes are missing. The lot size given in the instructions to the surveyors by John Collins changed during the first year. Nigel showed a copy of a document which has the date of 17 May 1782 at the end above John Collins’ signature, but has Sept. 11, 1783 on the cover page which adds to the complexity of clearly understanding how the survey and settlement proceeded.

The first lots surveyed or laid out were possibly/probably 120 acres due to the request in the initial instructions (a copy of which we have), but that was going to cause complications in the allocation to Loyalists: grants were made in increments of 50 acres for privates, 200 for NCOs, and 500 for officers. Further instructions must have been received altering the required lot sizes to 200 acres (but these instructions have not yet been acquired). (And that explains why some Loyalists received 1/4 of a lot!). Somewhere in the initial year either before or after the full original survey (again, the original field notes are missing), the lot sizes were significantly altered along with where the roads or road allowances were originally established.

In further analyzing early information, one discovers an unusual mix of measurements with ties to the east and west corners of the township along Lake Ontario. These tie measurements on the original plan are measured in perches rather than the rest of the plan being in chains. A perch was a holdover from the old French system of land measurement, and equaled 16.5 feet and the mix of perches and chains is a bit unusual. The chain, by comparison, was 66 feet in length — which was often also the width of the original road allowances (in Kingston Twp they were 40 feet originally).

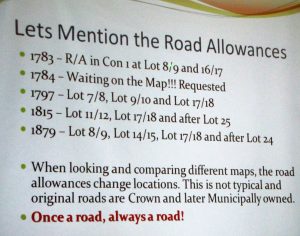

Digging more deeply into the historical information and looking at maps from progressive years, one can notice that road allowances seem to change in location and/or lot numbering actually changes which is quite unusual. Maps could have human errors in their creation, however certain concessions have lot numbers which do not align and can specifically be noticed in going north from Lot 25, which in concessions further up changes to lot 24. This can happen due to measurement anomalies, but again the alignment of the lots here is very unusual.

Other questions arise:

* Why does Division Street (running southerly) not continue straight and right to the lake? The original road allocation shown on some of the early maps should have it continue straight down (would be near the corner of Barrie and King), but it swung east along what is now West Street.

* King Street showed great variation even when first surveyed. Part of the problem, Nigel explained, is that magnetic compasses have a significant deviation along Kingston’s waterfront and as far out in the lake as south of Wolfe Island, due to a large underground deposit of iron. So when the survey crews laid out their chains in 1783 after driving in the first markers, they were possibly not heading in the directions they thought (certainly at the south east end of the township).

* He has also found some markers which do not appear to have been moved, but are in an unexpected place. Along the western boundary of Kingston Township, a marker labelled “C1” which possibly should have been at the northwest corner of Concession 1, Lot 1 is in fact short of the mark from a distance perspective. Does C1 mean 100 chains or Concession 1 and why is there a stone monument at this position? It is unusual since there was either a monument originally at 63.25 chains (120 acre lot) or 105.27 chains (but would be in the bay – 200 acre lot) or a witness to that point. Without the original notes we cannot tell with certainty why the post (stone marker) is planted there. It can be found northwest of the parking lot at Lemoine Point: take the path northwest and just past the lone tree on the left, go up the small trail to a small power line and turn right at the line and it will be ahead on the path.

Unfortunately the surveyors’ original notes and reports, and some maps, for Kingston Township are missing. They may be in the British Archives, but attempts to request a search for them have been unsuccessful. (The notes and reports for the survey of Pittsburgh Township are at Queen’s Archives.)

This certainly raised some interesting questions about the vagaries of Kingston Township’s original layout. Anne Redish pointed out that Michael Grass was first given land that would now include City Park and the Court House, but did not want that and eventually obtained land further west, around the present airport. Perhaps he and other prominent Loyalists persuaded the surveyors to alter the layout of certain properties? No one will ever know, but Nigel Day has found it an interesting puzzle, and plans to continue researching it.

Photos by Nancy Cutway. Thanks to Nigel Day for permission to photograph his slides, and for his careful review of my non-scientific interpretation of surveying terms.

May 12, 2015

We celebrated the arrival of spring with our annual banquet luncheon at the Donald Gordon Centre. The tables had been festively decorated with small Loyalist flags and an assortment of Loyalist-designed placemats, courtesy of member John Lynn Bell UE who contributed several different designs at the time of printing for a previous conference.

Note the mat with signatures of Lynn’s various UE ancestors and other individuals interacting with them. What a great idea! He simply photocopied a number of signatures, cut them out from the larger pages and placed them on one master page, then photographed it. You could do the same as a gift for grandchildren or other family members, as a way of bringing their ancestors to life.

Note the mat with signatures of Lynn’s various UE ancestors and other individuals interacting with them. What a great idea! He simply photocopied a number of signatures, cut them out from the larger pages and placed them on one master page, then photographed it. You could do the same as a gift for grandchildren or other family members, as a way of bringing their ancestors to life.

Loyalist ladies enjoying lunch.

Annette, Maureen and Jim Long UE

A good time was had by all. About 45 folks were able to gather for this mid-week event.

Former branch genealogist Eva Wirth was pleased to present Doris Wemp with her UE certification. Doris’s Loyalist ancestor is Hermanus See. It was also Doris’s birthday, so we were able to congratulate her with song.

Next, Barbara Bradfield UE introduced our speaker, Rev. William Hendry, whose talk was entitled “There Must Be a Better Way.” He compared the Loyalists with more recent groups of refugees created by conflicts around the world. As he said, “History is really a litany of fleeing persecution.” He spoke of the wish for negotiation and compromise in such cases, which leads us to wonder: what if George III’s advisors had accepted the wish of some American colonists for representation in the British parliament?

Next, Barbara Bradfield UE introduced our speaker, Rev. William Hendry, whose talk was entitled “There Must Be a Better Way.” He compared the Loyalists with more recent groups of refugees created by conflicts around the world. As he said, “History is really a litany of fleeing persecution.” He spoke of the wish for negotiation and compromise in such cases, which leads us to wonder: what if George III’s advisors had accepted the wish of some American colonists for representation in the British parliament?

Peter Davy UE (left) thanks Rev. Hendry (right) for his talk.

March 28, 2015

Sue Bazely, well-known archaeologist, spoke on Provincial Marine to Royal Navy: Archaeological Evidence of the War of 1812 at Kingston’s Naval Dockyard Sue pointed out that beginning in 1783, settlement of the Loyalists was concentrated along the St. Lawrence River, Lake Ontario and the west side of the Niagara River. There was a severe shortage of commercial ships available to move the Loyalists around and facilitate trade, so the Provincial Marine and their ships, stationed in Upper Canada after the American Revolution, were used for commercial transit to alleviate the shortage. The Provincial Marine was based at Carleton Island until 1789, when merchants lobbied for it to move to Kingston, to Point Frederick. By 1790 the Naval Dockyard was established. Four large gunships were built there between 1800 and 1812.

Sue Bazely, well-known archaeologist, spoke on Provincial Marine to Royal Navy: Archaeological Evidence of the War of 1812 at Kingston’s Naval Dockyard Sue pointed out that beginning in 1783, settlement of the Loyalists was concentrated along the St. Lawrence River, Lake Ontario and the west side of the Niagara River. There was a severe shortage of commercial ships available to move the Loyalists around and facilitate trade, so the Provincial Marine and their ships, stationed in Upper Canada after the American Revolution, were used for commercial transit to alleviate the shortage. The Provincial Marine was based at Carleton Island until 1789, when merchants lobbied for it to move to Kingston, to Point Frederick. By 1790 the Naval Dockyard was established. Four large gunships were built there between 1800 and 1812.

November 10, 1812 marks the date of Kingston’s only involvement in the War of 1812, a barrage from the gun batteries at Point Frederick, Murney’s Point and Missisauga Point against the ships of Commodore Isaac Chauncey of the US. In spring 1813 the Royal Navy under Sir James Yeo engaged Chauncey’s fleet again, and successfully blockaded Sackett’s Harbor, NY.

Meanwhile, since the start of the war there was a boatbuilding frenzy in the dockyard. HMS St. Lawrence was the largest ship with the most guns ever built on the Great Lakes. And the dockyard was the largest Royal Navy dockyard on fresh water, anywhere in the world.

The men also built blockhouses, five in a line along West/Sydenham streets and one on the east side of the Cataraqui River at Point Frederick and Fort Henry. Hundreds of civilian shipwrights and carpenters were brought from Quebec City to join local employees, and by 1814 there were up to 1200 staff at the Dockyard. Several structures were built that show up on various early maps, including a hospital 64×38 ft on a stone foundation and 3 other long, narrow buildings.

The civilians had to build their own shanties, mostly from scrap lumber – in 1815 there were apparently 34 of them before Commodore Owen had them extend the hospital yard northward and fix up some shanties while tearing down others. In 1819 Commodore Barrie urged them to get rid of the “dangerous wooden buildings” and substitute stone or brick buildings; in 1822 a row of 16 stone cottages was built.

Previous excavations in the 1960s had shown what little remains of the blockhouse and an artillery barracks, both of which were mostly obliterated by the 1840s erection of the Martello Tower on Point Frederick.

Previous excavations in the 1960s had shown what little remains of the blockhouse and an artillery barracks, both of which were mostly obliterated by the 1840s erection of the Martello Tower on Point Frederick.

In 2004 a new dormitory was to be built at RMC. This afforded an opportunity for archaeological investigations. They did find evidence of 1812 Encampments, with ash deposits from campfires, ceramics, large pieces of animal bones, glassware, musket balls and military buttons, and coins.

Excavation also uncovered a fireplace that probably came from one of the shipwrights’ shanties. Among the artifacts located there were some small figurines of saints or madonnas which might have belonged to a worker who was part of the recruitment from Quebec City. Another dig in 2007-08 around #10 of the 16 stone naval cottages found an earlier foundation, believed to be one of the 3 long structures shown on the 1815 map.

Excavation also uncovered a fireplace that probably came from one of the shipwrights’ shanties. Among the artifacts located there were some small figurines of saints or madonnas which might have belonged to a worker who was part of the recruitment from Quebec City. Another dig in 2007-08 around #10 of the 16 stone naval cottages found an earlier foundation, believed to be one of the 3 long structures shown on the 1815 map.

For many years it was thought that the 1812 hospital may have become today’s Commandant’s Residence, but the 2007 dig found the foundation of the hospital, located northwest of the current commandant’s residence — which likely started life as the surgeon’s quarters, set apart from the hospital. This dig also found a stone-lined drainage ditch meant to drain the hospital yard. An exploration of the former barracks and canteen buildings on the hill found an intact chimney base, carpenter’s tools, and close to 200 coins. Digging in the privy pit for the officers’ quarters produced much china, and many liquor bottles!

The Royal Navy dockyard at Point Frederick closed down in 1853.

During the business meeting, Clara Snook handed Treasurer Gerry Roney $100 raised over the past year by the Hospitality Committee, for the upcoming Heritage Fair.

January 24, 2015

Some 20 of us shared a potluck lunch. We were then joined by others coming for the meeting itself. After a brief discussion of branch business, we were privileged to hear Maxime Chouinard, the Curator of the Museum of Health Care housed in the Ann Baillie Building of Kingston General Hospital. Maxime explained that the impetus for the Museum came from Dr. James Low who began work on the project in 1988. In 1991 it opened to the public, and moved to Ann Baillie in 1999. The museum houses 40,000 objects including artifacts and documents dealing with doctors, nurses, and dental care.

Mr. Chouinard entitled his talk “The Doctor Will See You: Early medicine in Canada”. He pointed out that as late as the early nineteenth century, there were very few regulations on the practice of medicine, and very little scientific knowledge. Most physicians followed the theories of Hippocrates and Galen, predominantly the Theory of Humours: that the body was controlled by four “humours” — blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile — and sickness arose when the humours got out of balance.

Mr. Chouinard entitled his talk “The Doctor Will See You: Early medicine in Canada”. He pointed out that as late as the early nineteenth century, there were very few regulations on the practice of medicine, and very little scientific knowledge. Most physicians followed the theories of Hippocrates and Galen, predominantly the Theory of Humours: that the body was controlled by four “humours” — blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile — and sickness arose when the humours got out of balance.

[left] Handbook of Surgical Procedure by Stephen Smith – a fairly slender volume

The most common way to deal with bad humours was bloodletting, either by application of leeches or by cutting into the patient’s flesh. Maxime displayed a bloodletting kit from the 1840s which included a “scarificator”: a metal device with several concealed blades which cut into the skin when triggered. He said there was no understanding of how much blood a body contained or how much could be removed at one time. George Washington’s death was in part due to repeated bloodlettings and subsequent infection.

The most common way to deal with bad humours was bloodletting, either by application of leeches or by cutting into the patient’s flesh. Maxime displayed a bloodletting kit from the 1840s which included a “scarificator”: a metal device with several concealed blades which cut into the skin when triggered. He said there was no understanding of how much blood a body contained or how much could be removed at one time. George Washington’s death was in part due to repeated bloodlettings and subsequent infection.

Scarificator with blades raised

Infection was a major problem because they did not sterilize equipment between uses. Another way to let out blood was by cupping: lighting a candle to create a vacuum inside a glass cup by burning the air inside. The cup then sucks the skin, creating an inflammation, but not a burn. The red-blue color of the skin which resulted was thought to be the bad humours being attracted to the surface.

Maxime also displayed a saw and knife from an amputation kit. Amputations were common, and surgeons prided themselves on how quickly they could amputate a limb (because there was no anaesthetic, and therefore the patient would suffer for a shorter time). Dr. James Douglas, a surgeon in Quebec City (and father of the James Douglas for whom one of Queen’s University’s libraries is named) claimed he could perform an amputation in under a minute.

Left: A trepan was used to open holes in the skull.

Right: Maxime Chouinard demonstrates a dental molar extractor.

By mid-19th century doctors came to understand the existence of disease-causing organisms. During the cholera epidemics of the 1830s, it was thought that heating air would disperse the disease and many cities set out barrels of burning tar in a vain effort to dispel the “vapours”. In contrast, in 1854 a Dr. John Snow observed that cases from another outbreak in London were all among people taking water from the same well, and it was realized that cholera was in fact water-borne.

Joseph Lister urged doctors to wash their hands between patients, and Louis Pasteur in 1859 disproved the theory of spontaneous generation of infection, demonstrating that organisms instead came from outside (air, water or contact) into a body. Scientific medicine came into being.

A most informative talk. We look forward to the next exhibit at the Museum of Health Care; a display on World War I Health Care will open next month.

All photos January 24 by Nancy Cutway